A Beginner’s Guide To Curriculum Development At Primary School: The Lessons I’ve Learnt About How To Plan And Sequence The Curriculum

Knowing how to develop a curriculum at primary school can feel like an impossible task, but after attending a training session specifically on curriculum development, Year 6 teacher and Third Space author Sophie Bartlett is here to help you do just that. In this blog you’ll find her key takeaways from this event and some top tips you can use when developing your own primary curriculum.

“‘You can always Google it’ is the most dangerous myth in education today.” – Dylan Wiliam

A few disclaimers before we start:

- In no way do I profess to be a curriculum expert

- In no way do I profess to be a cognitive science expert

- In no way do I profess to be a teaching expert

- In every way do I profess to be a fan of Clare Sealy and Andrew Percival’s work on the curriculum, the influence of cognitive science on its development, and the new style of delivering the curriculum that will inevitably follow (for me, anyway!)

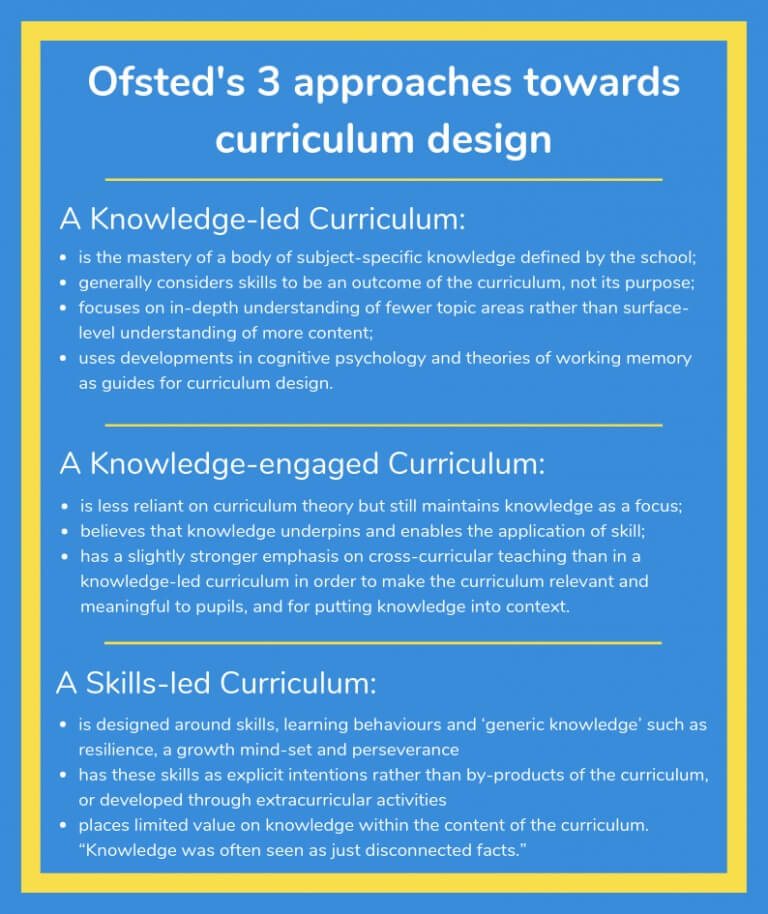

Ofsted’s approach to curriculum development

In September 2018, Amanda Spielman discussed Ofsted’s findings from their recent curriculum research, curriculum design and the new Ofsted framework 2019.

She stated that:

“too many teachers and leaders have not been trained to think deeply about what they want their pupils to learn and how they are going to teach it… Ultimately, the curriculum is the yardstick for what school leaders want their pupils to know and to be able to do by the time they leave school. It is therefore imperative that the new inspection framework has curriculum as a central focus.”

In Ofsted’s curriculum research, three types of approach towards curriculum development in education, and their design (as characterised below by Spielman, 2018) were identified: knowledge-led, knowledge-engaged and skills-led. Below we will discuss each one in more detail.

See also: Ofsted crib sheets

A knowledge-led curriculum:

- is the mastery of a body of subject-specific knowledge defined by the school;

- generally considers skills to be an outcome of the curriculum, not its purpose;

- focuses on in-depth understanding of fewer topic areas rather than surface-level understanding of more content;

- uses developments in cognitive psychology and theories of working memory as guides for curriculum design.

A knowledge-engaged curriculum:

- is less reliant on curriculum theory but still maintains knowledge as a focus;

- believes that knowledge underpins and enables the application of skill;

- has a slightly stronger emphasis on cross-curricular teaching than in a knowledge-led curriculum in order to make the curriculum relevant and meaningful to pupils, and for putting knowledge into context.

“Most of the curriculum leaders from the knowledge-led and knowledge-engaged schools stressed the importance of the subject as a discipline. They provided pupils with subject-specific vocabulary and knowledge that allowed them to build links and enhance their learning across other subjects.” (Spielman, 2018)

A skills-led curriculum:

- is designed around skills, learning behaviours and ‘generic knowledge’ such as resilience, a growth mind-set and perseverance;

- has these skills as explicit intentions rather than by-products of the curriculum, or developed through extracurricular activities;

- places limited value on knowledge within the content of the curriculum. “Knowledge was often seen as just disconnected facts.”

“Nearly all the curriculum experts we spoke to considered their local context and pupil needs when building their curriculum… The experts tended to talk about giving their pupils the knowledge or skills that were lacking from their home environments as a core principle for their curriculum and tailored their approach accordingly. Many of the leaders in these schools saw a knowledge-led approach as the vehicle to address social disadvantage.” (Spielman, 2018)

Spielman concluded her findings with the following statement:

“Without doubt, schools need to have a strong relationship with knowledge, particularly around what they want their pupils to know and know how to do. However, school leaders should recognise and understand that this does not mean that the curriculum should be formed from isolated chunks of knowledge, identified as necessary for passing a test.

A rich web of knowledge is what provides the capacity for pupils to learn even more and develop their understanding. This does not preclude the importance of skill. Knowledge and skill are intrinsically linked: skill is a performance built on what a person knows.”

KS2 Maths Knowledge Organiser & Quiz

Download this KS2 Maths Knowledge Organiser that is perfect to use both before and after SATs, and use the accompanying quiz to identify knowledge gaps in your class!

Download Free Now!Developing a curriculum for longterm learning

The remainder of this article draws on everything I learnt from attending a (now high in-demand!) training session run by Clare Sealy (a primary head-teacher in Bethnal Green – @ClareSealy) and Andrew Percival (a deputy head leading on curriculum – @primarypercival) all about curriculum development.

Although it was emphasised that there is no ‘Ofsted-approved’ curriculum (Spielman says that Ofsted “need to assess a school’s curriculum in a way that is valid, fair and reliable, and that recognises the importance of schools’ autonomy to choose their own curriculum approaches”), Sealy and Percival focused on how to build a curriculum that prioritised improving children’s long-term memories, supported by Kirschner, Sweller and Clark’s theory that “if nothing has been changed in long-term memory, nothing has been learned”.

Clare Sealy has written all about cognitive load theory in the classroom and long-term memory in the primary school context.

The scientific cognitive load theories behind this approach are fascinating, but I can not do them justice here.

I am here to share what I’ve learnt about a knowledge-led/-engaged/-focused/-rich (pick your poison) curriculum and why I’m so excited to start developing one in my school.

However, perhaps once you’ve read my ramblings (and hopefully been infected with my enthusiasm – or at least been made mildly curious!), I strongly advise – no, implore – you to read both Clare and Andrew’s blogs for a more coherent, evidenced and intellectual account of their ideas around curriculum development.

My ‘take-aways’ from the training: the 12 things you need to know about curriculum development

There were of course a number of things I took away from the training course, but here are some of the key highlights you should take note of before creating your own curriculum development process.

1. Knowledge Is GOOD

This is a short but sweet takeaway.

When creating a curriculum, keep the “Matthew effect” in mind.

This is that the (knowledge) rich get richer and the (knowledge) poor get poorer.

It’s a simple concept, but one that can often be forgotten about so make sure you note it down!

2. It’s essential that our children are exposed to broad knowledge through our curriculum

Daniel Willingham states that “reading tests are knowledge tests in disguise”.

See a study here where ‘good’ readers with very little baseball knowledge and ‘poor’ readers with substantial baseball knowledge both sat a reading assessment about baseball; the results show that the latter group performed more highly, prompting Willingham to conclude that “teaching content IS teaching reading” (2012).

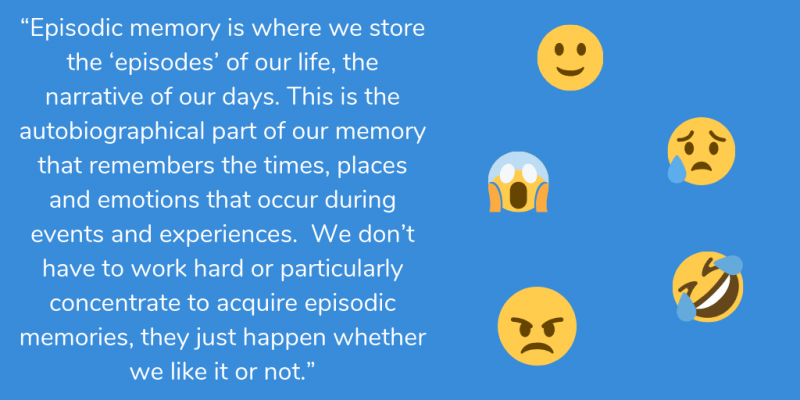

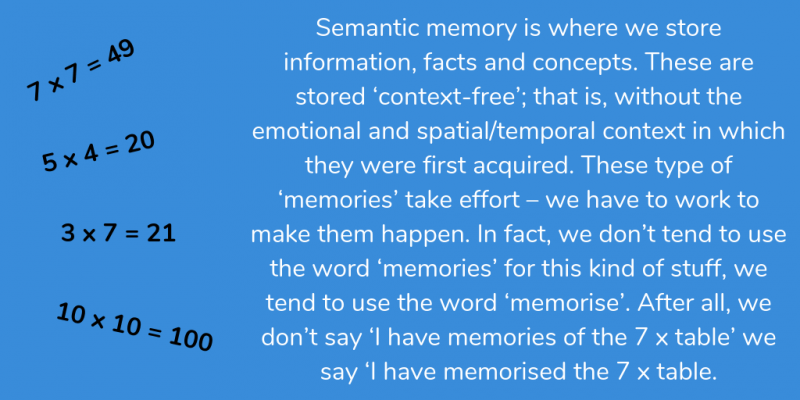

3. Episodic and semantic memory are different

There is an important differentiation to be made between episodic memory and semantic memory, defined here by Clare Sealy:

Episodic memory is tagged with context.

A child may remember learning division in a Year 4 classroom with Mrs Smith on a rainy day, but remove that context and put them in a Year 5 classroom with Mr Jones in the middle of summer and suddenly it’s gone. (This is where I began to recognise my typical Year 6 outburst of “You said they learnt that in Year 4/5… are you sure? Because they can’t do it now!”)

4. “Wow” lessons are unnecessary and potentially harmful to learning

When it comes to “wow” lessons, children remember the experience (in their episodic memory) rather than the actual learning (which hasn’t made it to their semantic memory).

Remove the context (sunny day, throwing paper planes outside (you decide what the learning objective could be for that one – angles? gravity?), choosing your own teams, writing with chalk on the floor) and the learning is also gone.

Developing memory, not rich memories, is key in developing problem solving and creativity. (This comes with the caveat that of course episodic memory is still important, especially for those lacking in life experiences).

5. All instructions should have a specific purpose

“The aim of all instruction should be to improve long-term memory. If nothing has been changed in long-term memory, nothing has been learnt.”

(Kirschner, Sweller & Clarke).

Essentially, effective teaching = minimising the overload of working memory to maximise retention in long-term memory.

6. There are a number of poor proxies for learning

In 2013, Robert Coe identified a number of poor proxies for learning and they are:

- students are doing lots of work

- students are engaged

- students are getting feedback

- the classroom is calm

- students have given correct answers

Greg Ashman has also written a good blog about proxies for learning which I would recommend reading.

7. We need to focus on augmenting remembering

There are three easy traps to fall into when delivering content that we expect children to remember:

Trap 1: learning never makes it to the working memory if it is made “over-exciting”

For example unless you choose wisely the maths game you play with children they are more likely to remember the rules of the game rather than the actual maths.

Trap 2: content is easily forgotten if the working memory is overwhelmed.

Read more: Interleaving: what it is and how to use it to improve learning in the classroom

Break down steps into the smallest chunks possible to help children remember them.

Trap 3: children are unable to recall content from their memory.

Fortunately, there is a way to solve this and it is to use retrieval methods! (Retrieval comes from the French retrouver, meaning to find again). The struggle of trying to retrieve something strengthens memory. All knowledge is hiding somewhere in your long-term memory – you just have to play hide and seek with it! Clare Sealy has also written all about how to use retrieval practice in the classroom.

Read more: Spiral curriculum

8. Teach less but practise more

None of this “but I have no time to practise because I have too much to teach!”

9. It’s important to understand the difference between declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge

Another important differentiation to make is of that between declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge, the former meaning facts, the latter meaning “skills” (essentially putting declarative knowledge to work).

Skills cannot be detached from context; for example, an observation in science is very different to an observation in art!

The ‘knowledge versus skills’ argument is essentially about the extent to which generic skills are transferable from one context to another.

10. Knowledge doesn’t always mean understanding

To understand something means having lots of well-connected, well-organised knowledge.

You can know but not understand, but you can’t understand and not know. (“Knowledge-rich” does NOT mean lecturing at children!)

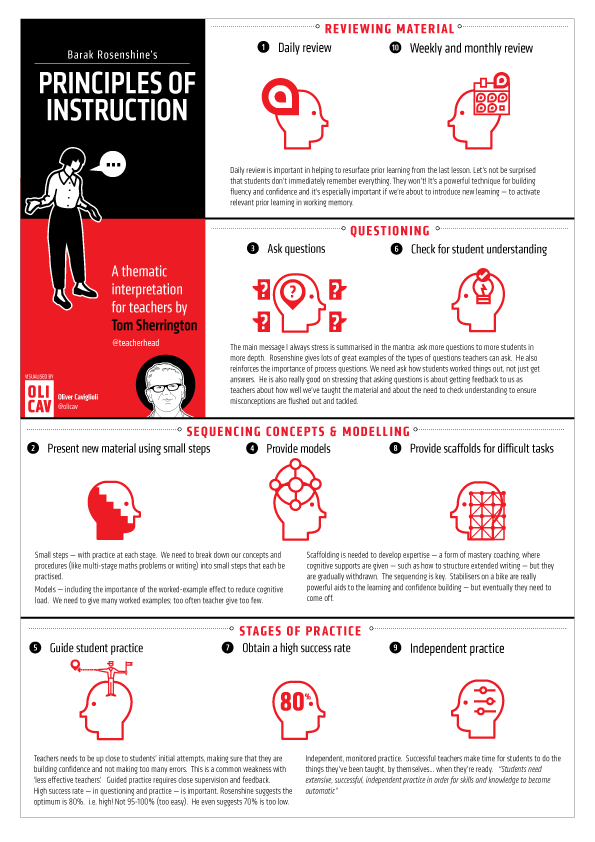

11. Make Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction (2012) Your Teaching Bible

Oliver Caviglioli (@olicav) has made a brilliant poster of Rosenshine’s principles of instruction which can be downloaded for free.

12. Work towards a 3D curriculum

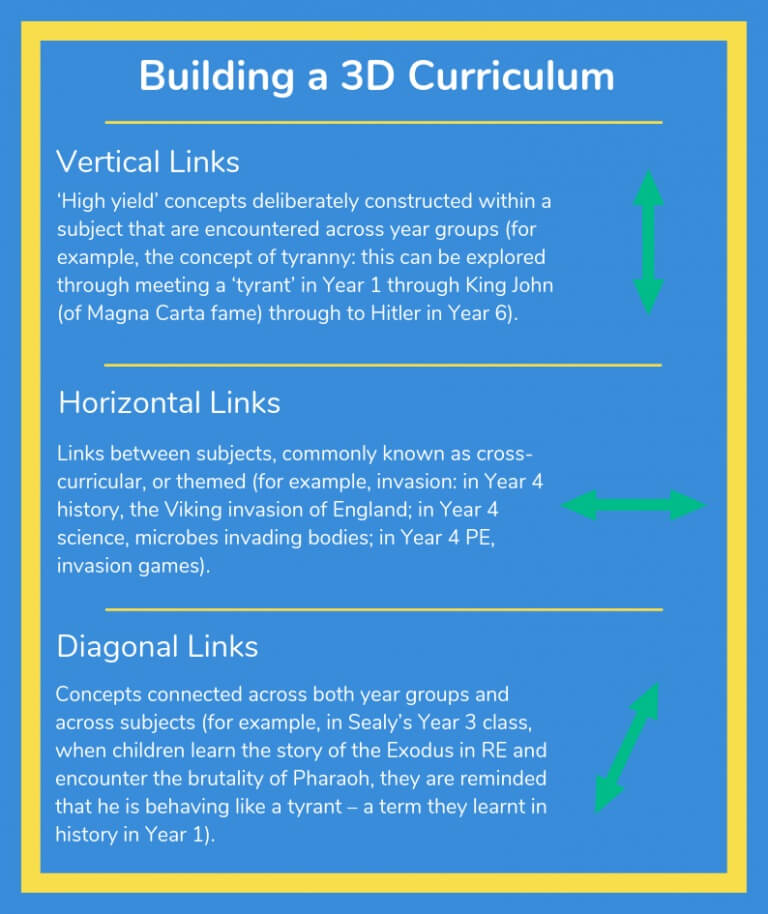

Building a 3D curriculum (a term defined by Clare Sealy as a curriculum that promotes remembering) is important in order to make vertical, horizontal and diagonal links, which Sealy explains below.

Vertical links: ‘high yield’ concepts deliberately constructed within a subject that are encountered across year groups (for example, the concept of tyranny: this can be explored through meeting a ‘tyrant’ in Year 1 through King John (of Magna Carta fame) through to Hitler in Year 6).

Horizontal links: links between subjects, commonly known as cross-curricular, or themed (for example, invasion: in Year 4 history, the Viking invasion of England; in Year 4 science, microbes invading bodies; in Year 4 PE, invasion games).

Diagonal links: concepts connected across both year groups and across subjects (for example, in Sealy’s Year 3 class, when children learn the story of the Exodus in RE and encounter the brutality of Pharaoh, they are reminded that he is behaving like a tyrant – a term they learnt in history in Year 1).

How to develop a curriculum: the next steps

The curriculum development process isn’t easy, but there are things you can do to ensure that things happen as smoothly as possible in your school.

As you may have gathered, redesigning the curriculum is an immense task, and one that ideally needs all staff on board and willing to contribute.

My school is in exactly that position. Our initial idea was for me and a colleague to take on the brunt of the work (especially as we were the only two in a very small school of only four classes to attend the course), but on reflection we decided that in order to successfully create a 3D-style curriculum, we would need the input, knowledge and experience of all staff.

As I discussed with another attendee to this training, this in itself seems unmanageable – where do you find the time to get all your staff together for the amount of time it would take to tackle a task like this?

Where do you even begin?

I don’t have the answers, but this is where we (referring to me and my colleague) are going to start (and I’ll hopefully be tweeting our journey!). Take a look at my twitter account @_MissieBee for updates.

We started with assessing all the non-core subjects

We looked at all subjects (including science) through the lens of which, would take us the longest to create a curriculum/body of knowledge for. We took into account how much content each subject would have (an argument in itself), their relative ‘importance’ (another long discussion!) and our own current combined subject knowledge.

This roughly reflects what we came up with:

| Current Curriculum subject coverage | |||

| Good | Not good enough yet | ||

| National Curriculum Content | Heavy | Science | Geography History |

| Light | MFL Music PE RE | Art Computing DT |

Then it was time to get subject specific

For our next steps we:

- Identified subjects for which we have already bought schemes of work that would still fit with our ideal new curriculum and are therefore not a priority (for the next academic year anyway) – for us, this removes PE, RE, computing and music.

- We planned to start with the good subject knowledge/content-light subjects OR subjects that are content-light/have regular slots in our timetable as this seemed logically the easiest place to begin. For us, this means MFL, DT or art.

“Planned” is the operative word here, as our first meeting is subject to the regular delays that come with life in a primary school, and in this meeting we will pick one of the aforementioned subjects to begin mind-mapping our initial ideas for:

- how it can be used to create vertical, horizontal and diagonal links across the curriculum;

- what we might include in our body of knowledge for that specific subject discipline;

- and what progression could look like in that specific subject discipline throughout the school.

After having started the planning process, we will then take this to the rest of the staff to build it into a scheme of work with which we are all happy. In some subjects, we can start by building knowledge organisers (like the one I made for a Year 6 maths class) for the children.

Read more on knowledge organisers from teachers I admire here:

KS2 Maths Knowledge Organiser & Quiz

Download this KS2 Maths Knowledge Organiser that is perfect to use both before and after SATs, and use the accompanying quiz to identify knowledge gaps in your class!

Download Free Now!To achieve this with all foundation subjects before the next academic year would be both unmanageable and foolish as we would obviously like to trial this new method in only one or two subjects before following it through to the rest of the curriculum.

As it stands, our plan is to have perhaps two subjects ready for next September.

Preparing to overcome obstacles: What could go wrong when we are developing our curriculum

With all new strategies come potential pitfalls.

We are bound to experience some we have not foreseen along the way, but currently, this is what we are predicting may hold us back and how we plan to overcome it.

| Barrier | Solution |

| Staff subject knowledge | Work to individual strengths – different colleagues take the lead depending on the subject. |

| Staff ‘buy-in’ | Dedicated staff meetings, encourage staff to read blogs (as mentioned in this article), trial with one subject and hopefully see the impact! |

| Time | Use staff meetings and INSET days (NB: this is ultimately going to be the most challenging one. Luckily, I am personally very interested in this and happy to do it in my own time, but I realise that won’t always be the case). |

I’ll be tweeting our curriculum redesign journey from @_MissieBee, so please let me know if you have any advice or questions for me – we could use all the help we can get, and I’d love to be able to help others too.

Clare and Andrew are brilliantly helpful and responsive on Twitter, so please do read their blogs and ask them if you have any more questions, especially as this whole journey was inspired by them.

We’re all in this together!

Read more

DO YOU HAVE STUDENTS WHO NEED MORE SUPPORT IN MATHS?

Every week Third Space Learning’s specialist school tutors support thousands of students across hundreds of schools with weekly online 1 to 1 maths lessons designed to plug gaps and boost progress.

Since 2013 these personalised one to one lessons have helped over 150,000 primary and secondary students become more confident, able mathematicians.

Learn about the scaffolded lesson content or request a personalised quote for your school to speak to us about your school’s needs and how we can help.

![The 12 Most Important Ofsted Safeguarding Questions and Answers [2024]](https://thirdspacelearning.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/safeguarding-questions-and-answers-1-180x160.jpg)