Published in European Police College (CEPOL) e-library, scientific collection, Hungary

https://www.cepol.europa.eu/index.php?id=e-library

Counterinsurgency in the Punjab - A Lesson for Europe

Peter A. Kiss

"War no longer exists." Rupert Smith, the distinguished British general begins his review1 of

the recent past and present of military affairs with this provocative statement. While he may

have been exagerating a little for dramatic effect, interstate war on a massive, industrial scale

has certainly been a rare occurence since the end of World War Two. India-Pakistan, IraqIran, Israel and her neighbors, Iraq against the coalitions, NATO against Yugoslavia - the list

is fairly short, compared to previous centuries. Intrastate war - rebellion, insurgency, civil war

- has become the dominant form of armed conflict. The whole paradigm2 of conflict has

changed, and in spite of their potential advantages in resources, firepower, mobility,

manpower, leadership and training, the state's security forces have often done quite poorly in

this new paradigm.

Europe has also had its share of insurgencies, from Northern Ireland, through Italy's Anni di

Piombo and the Paris Intifada, to Kosovo, 1999. Economic, social and political developments

are likely to lead to further insurgencies, therefore Europe's security forces must be prepared

to deal with them - but so far their record of success and failure has been mixed at best. The

study of successful counterinsurgency campaigns offers useful insights and assists in

developing counterinsurgency doctrine that is appropriate for European conditions. Focusing

1

Smith, Rupert: The Utility of Force The Art of War in the Modern World, 2005. Penguin Books, London, 428

p.ISBN 0-141-02044-x

2

The new paradigm has had many names already: modern warfare, revolutionary warfare, low intensity conflict,

counterinsurgency, unconventional war, fourth generation warfare, asymmetric warfare, just to list a few.

Asymmetric warfare seems to be getting the most traction at present. Its theoretical foundations have been laid

out in a series of articles and essays, the best of which are: Lind, William S.: "Understanding Fourth Generation

War," Military Review, Fort Leavenworth, KS, 2004. Sep-Oct, pp 12-16,

http://calldp.leavenworth.army.mil/scripts/cqcgi.exe/@ss_prod.env?CQ_SESSION_KEY=SWOSAVANWFYR

&CQ_QH=125928&CQDC=9&CQ_PDF_HIGHLIGHT=YES&CQ_CUR_DOCUMENT=1', Lind, William S.;

John F. Schmitt, Gary I. Wilson: "Fourth Generation Warfare: Another Look," Marine Corps Gazette, Quantico,

VA, 1994. Dec, pp. 34-37 http://www.d-n-i.net/fcs/4GW_another_look.htm, Lind, William S.; Keith

Nightengale; John F. Schmitt, Joseph W. Sutton, Gary I. Wilson: "The Changing Face of War: Into the Fourth

Generation," Marine Corps Gazette, Quantico, VA, 1989. Oct, pp. 22-26 http://www.d-ni.net/fcs/4th_gen_war_gazette.htm, Hoffman, Frank G: Conflict in the 21st Century: The Rise of Hybrid Wars,

2007. Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, Arlington, VA, 72 p.

www.potomacinstitute.org/publications/Potomac_HybridWar_0108.pdf

1

�on a successful counterinsurgency campaign in India, this paper identifies some key lessons

that are applicable in the European environment.

The reader has every right to ask why this author wants to analyze a conflict that ended 15

years ago, and whose location, participants and root causes are not familiar for a European

audience. Today's problems are the events in Afghanistan and Iraq: they directly affect

Europe (primarily because European forces are there in large numbers), and they raise a

number of issues (for example private military companies, heavily armed religious and tribal

militias) that were not a problem for the Indian security forces. Nevertheless, on at least three

counts the Indian experience in counterinsurgency seems more appropriate for the European

political and social environment, than anything Afghanistan or Iraq can offer:

The expeditionary forces in Afghanistan and Iraq (and to a lesser extent the Afghan and

Iraqi governments) are trying to import an alien political culture - primacy of individual

rights, parliamentary democracy, freedom of conscience, secularism that separates religion

and state - and force it on unwilling and not very receptive societies. In contrast, the

security forces in the Punjab protected the democratic traditions and unity of India against

the efforts of radical a separatist minority trying to impose a theocratic dictatorship. In

Europe's fourth generation conflicts the stake will also be the preservation of the states'

unity and the European traditions of secularism and democracy.

In Afghanistan and Iraq the very presence of the expeditionary forces is one of the major

causes of the insurgency - and this distorts the social and political characteristics of the

conflict, as well as the road to solution. The expeditionary forces exercise power in a

foreign land over an alien population; they are not subject to the local laws, and their rules

of engagement allow them broad freedom to employ deadly force and other coercive

measures - these conditions hardly differ from those of the colonial wars of the 19th

century. In contrast, in the Punjab it was the Indian security forces, especially the Punjab

Police (whose personnel was over 2/3 Sikh) that fought against the Sikh insurgents. They

were subject to the very same Federal and local laws that applied to the local civilians. In a

fourth generation conflict on their own territory the European states will also want to

prevail using their own security forces: In most European states the very presence of

foreign troops is a sensitive issue; if they engage in combat operations, that may lead to

parliamentary crisis.

2

�In Iraq and Afghanistan the military forces take the lead in fighting the local insurgencies.

India's security forces have been moving away from that solution: the contribution of the

military is invaluable, but clearly it is the police and the internal security troops that play

the decisive role. Instead of firepower-heavy military tactics they rely on tactics and

procedures that are a hybrid between police and military. In some European countries the

constitution prohibits the deployment of military forces for internal security duties; in

others, the possibilities for their deployment is strictly limited, so counterinsurgency will

have to be fought by the police and paramilitary forces.

India's Counterinsurgency Experience

Modern India's history, practically from the very first day of independence, is also a history of

almost ceaseless fourth generation conflicts:3 armed independence movements in Nagaland,

Mizoram, Manipur, Assam, Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir; leftist-communist-Maoist

rebellions in West Bengal, Andra Pradesh, Madia Pradesh, Bihar and in the southeast. In these

conflicts the Indian security forces have had some reverses, but they have also achieved some

impressive successes - probably more than any other country in the world.

In the 1950's and 1960's the security forces still relied on counterinsurgency doctrine4 derived

from British, French and American experience: counterinsurgency operations were conducted

by the Army; the population was moved to protected villages (much of the time against its

will); in the regions thus depopulated free-fire zones were declared and search and destroy

operations were mounted to finish off the insurgent organizations. In the 1970's Indian

officers gradually came to the conclusion, that European counterinsurgency procedures,

which may be effective, and may be appropriate for colonial expeditionary forces, cannot be

3

Independent India's first war was an insurgency in Kashmir that had been fomented by Pakistan. The

insurgency developed into a war with Pakistan and led to the division of Jammu and Kashmir that persists to

this day.

4

Unless otherwise stated, throughout this study the term "doctrine" will be used in the sense of "a body of

knowledge or instruction, a generally followed practice," rather than as bound volumes of officially approved

documents, rules and regulations.

3

�applied in an internal conflict, against fellow citizens - often friends or brothers.5 This

principle has become an organic part of the Indian Army's doctrine.6

Today, the goal of the Indian government is "resolution" of an insurgency, rather than its

"suppression;" state-consolidation, rather than enforcing central authority through armed

force. India's politicians are well aware, that insurgencies do not break out all by themselves serious, general and long-lasting injustice, ethnic or religious grievances, social and economic

inequality, corrupt and incompetent governance (but usually some combination of all these) is

required for the average citizen to give up his normal, everyday life, grab a weapon and risk

his life in a fight that seems hopeless. They know that an insurgency can be suppressed by

brute force, but handling its political and economic root causes yields less costly and longer

lasting results. And they also realize that only the security forces can create the atmosphere

that is conducive to a political compromise: the non-military elements of a counterinsurgency

strategy will not have any success, unless the uncompromisingly extremist elements are

destroyed and active resistance is broken. Accordingly, Indian counterinsurgency (or

"insurgency resolution") doctrine rests on three pillars:

Its first pillar is the long term presence and employment of significant armed force, in

order to create the security and stability necessary for a peaceful solution. Following the

principle of "least possible force," the security forces do not employ artillery or air strikes

against the insurgents, even if it means accepting heavier casualties. Military pressure is

constant: they realize that intermittent force has a markedly reduced effect, because the

insurgents can easily adapt to the rhythm of the security forces. Local police and the forces

deployed in densely populated areas isolate the population from the insurgents, and

provide them security. They also organize local militias to involve the population in the

fight against the insurgents. Active and effective intelligence effort guarantees surgical

precision - and thus a minimum of collateral casualties - of operations. A very important

element of the intelligence effort is the network of former insurgents who rallied to the

government's side. Control of the borders prevents foreign support from reaching the

insurgents. Numerous small-scale operations - frequent and aggressive patrolling, cordon5

Jafa, Vijendra Singh: "Counterinsurgency Warfare The Use and Abuse of Military Force," Faultlines, New

Delhi, India, 1999, http://satp.org/satporgtp/publication/faultlines/volume3/Fault3-JafaF.htm

6

Indian Army Doctrine, Headquarters Army Training Command, 2004. Shimla, India

http://wikileaks.org/wiki/Category:Series/Indian_Army_Doctrine_2004, pp. 68-75

4

�and-search, checkpoints - create territorial dominance. In these operations internal security

troops,7 whose organization, equipment, doctrine and tactics are optimized for

counterinsurgency, play an increasingly important role.

Reinforcement of local political structures is the second pillar. The central (federal)

government, the local political elite and the security forces cooperate in creating political

processes that visibly increase the role and decision-making powers of the local

government. Local elections - which are held on schedule, even under the threat of

insurgent violence - serve to legitimize local political structures. The goal is to convince

the local population that the benefits of working within the existing political system far

exceed those outside it. As befits the world's most populous democracy, in the relationship

between the political regime and the security forces the latter play the subordinate role.

India's disciplined generals have observed this principle for decades, even though the

political leadership often makes decisions that adversely affect operational efficiency (e.g.

operations can be halted in mid-stride), or compromise hard-won successes (e.g. hasty

political compromises with the insurgents may be sought).

The third pillar is economic development of the affected region. The goal is to reduce the

socio-economic roots of the insurgency: unemployment, geographic distance and isolation,

primitive infrastructure, lack of development assistance. By spending money to alleviate

these problems, the government in effect tries to "buy off" the social foundation of the

insurgency (the disaffected population), as well as its ideological motors (the local

intellectuals).

This doctrine has been developed over a period of decades and allowed the Indian security

forces to achieve some notable successes. They made some mistakes in the course of

particular insurgencies, they had some reverses. In some cases resolution took a long time,

due to faulty analysis or wrong decisions - but so far they have always managed to find the

right combination of military and non-military measures and the right balance between

incentives and coercion, rewards and punishments.

7

According to official Indian terminology these are "paramilitary" forces. Some come under the Ministry of

Home Affairs, some under Defense. The three largest are the Assam Rifles, The Rashtriya Rifles and the

Border Security Force - altogether 300 battalions. The battalions have six rifle companies instead of the usual

four, and do not have heavy weapons.

5

�Background to the Punjab conflict

The Punjab is the Northwest

region of historical India, and the

cradle of South-Asian

civilizations. The Harappa culture

developed here; many of the Hindu

holy books and epics were

composed here (the Rig Veda, the

Upanishads, the Ramayana, some

of the Puranas). As the wheel of

historical fortune turned, the

Punjabi-speaking Indo-Aryan

natives lived under Hindu, Jaini,

Buddhist, Macedonian, Persian,

Arab, Turkic, Mughal, Baluchi,

Sikh or British rule. When India

became independent (1947-48),

Indian Punjab

the Punjab was divided. Its

western 4/5th, where the population was predominantly Muslim, went to Pakistan. The

eastern 1/5th, where the majority was Sikh and Hindu, went to India. The Sikhs - worried

about their unique culture, language and religion disappearing in the surrounding Hindu sea demanded a

separate state. Their demand was granted in 1966, when the Punjab was further divided:

Haryana and Himachal Pradesh states were created from the districts where Hindus and the

Hindi language were predominant. The Sikh-majority districts retained the Punjab name and

became a separate state, where the Punjabi language and Sikh culture and religion could

flourish.

6

�A number of theories have been advanced to identify the root causes of the insurgency: the

negative social and economic consequences of the "green revolution;"8 revival of religious

fundamentalism; politicization of the Sikh religion; conflict between the main Sikh political

organization, the Shiromani Akali

Dal and the Congress Party, which

was dominant in the federal

parliament; underhanded

machinations of the prime minister

(Indira Gandhi); centralization

attempts by the federal

government; incitement of the Sikh

diaspora in Europe and Canada;

Pakistan's territorial ambitions.9

But complex social processes

hardly ever have a single driving

factor, and the Punjab insurgency

is no exception. All the above

reasons contributed to the situation

that developed at the end of the

1970's: mutual recriminations

between the federal government

and the Sikh political elite became

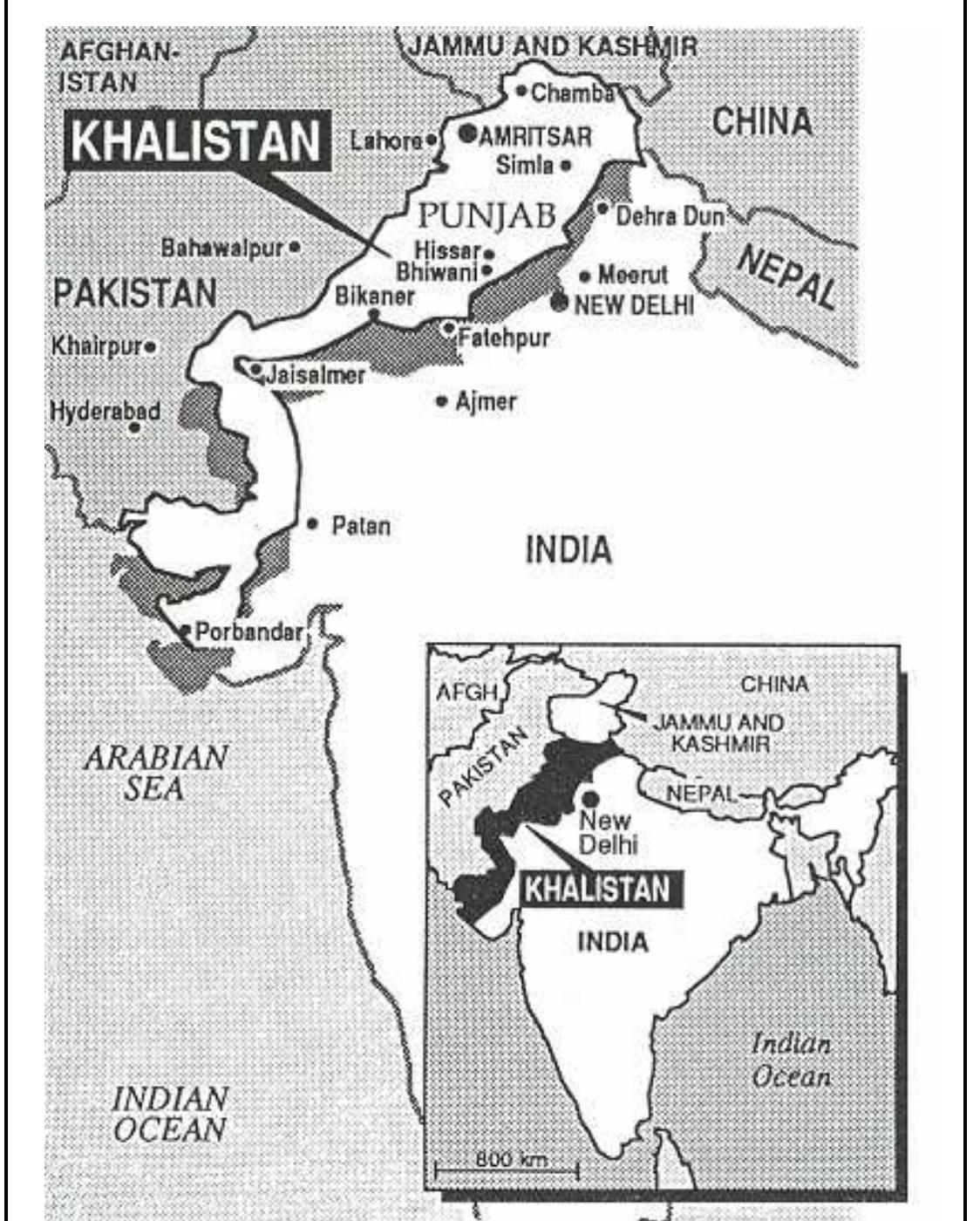

Map of one version of independent Khalistan.

Source: http://www.shaheedkhalsa.com/maps.html

daily events; there was no

8

The "green revolution" was a true revolution in agriculture: new strains, new cultivation processes, fertilizers,

pesticides and herbicides resulted in 1,000 percent increase in agricultural productivity between 1960 and

1990. In the third world this in turn led to a 20 percent reduction in famine, a 25 percent increase in calorie

intake and a significant increase in incomes. At the same time it also led to polarization in traditional agrarian

societies: the new processes and new strains required significant investment, which many familyes could not

afford - while some farmers became rich, many others lost their farms altogether.

9

Gill, Kanwar Pal Singh: The Knights of Falsehood, Har-Anand Publications, New Delhi, 1997,

http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/publication/nightsoffalsehood/index.html; Gill, Kanwar Pal Singh: "Endgame In

Punjab: 1988-1993," South Asia Terrorism Portal, 2001

http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/publication/faultlines/volume1/Fault1-kpstext.htm; Kang, Charanjit Singh:

"Counterterrorism: Punjab, a Case Study," 2005. Simon Fraser University, Burnamby Mountain, BC, Canada,

234 p. http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/dspace/retrieve/726/etd1604.pdf; and Mahadevan, Prem: "The Gill Doctrine A

Model for 21st Century Counter-terrorism?" Faultlines, Volume 19, April 2008.

http://satp.org/satporgtp/publication/faultlines/volume19/Article1.htm

7

�compromise between the opposing views, and the idea of a sovereign Sikh state (Khalistan)

was broached. A small group of Sikhs started demanding the creation of Khalistan: an

independent, theocratic state between India and Pakistan, and used violence to suppress the

voice of those who disagreed with their goals.

Space-Forces-Time-Intelligence Analysis

Space. The flat, open, cultivated terrain of the Punjab and its low level of urbanization are an

inhospitable environment for either rural or urban guerrilla warfare.

The state's 50,362 km2 area is primarily flatland. In the northeast, along the Himachal

Pradesh border the plains turn into rolling hills - the first slopes of the Himalaya's foothills.

Vegetation cover is primarily intensively cultivated crops, only about 30,000 km2 is forest.

The road and rail network - infrastructure in general - is the best in India.

According to census data the population was just above 17 million at the beginning of the

conflict, and just above 20 million at its end. Less than one third (28-29 percent) lived in the

150 cities. Three cities had population over 1 million, nine over 100,000. Sixty percent of the

population was Sikh, 37 percent Hindu, the remaining 3 percent Christian, Jaini and Muslim.

The "social terrain" was no more hospitable environment for insurgency than the physical.

The Sikhs were not subject to discrimination either in the Punjab, or elsewhere. They could

practice their religion without restriction, their temples (the gurudwaras) were found in every

Indian city and most villages. As sober, hard-working and thrifty people, they could find

employment anywhere in India in any position they were qualified for. But in India's unique

political environment modern, well-functioning democratic institutions exist side-by-side with

ancient social phenomena (caste system, arranged marriage, religion-based legal exemptions).

Political violence, violence between religious communities, ethnic groups and castes is quite

common. This did not affect the Sikhs any more or any less than any other community, and

the relationship between Sikhs and Hindus was quite good.

In spite of these drawbacks the separatist movement flourished for years, and during the 12

years of insurgency it came close to success on two occasions.

8

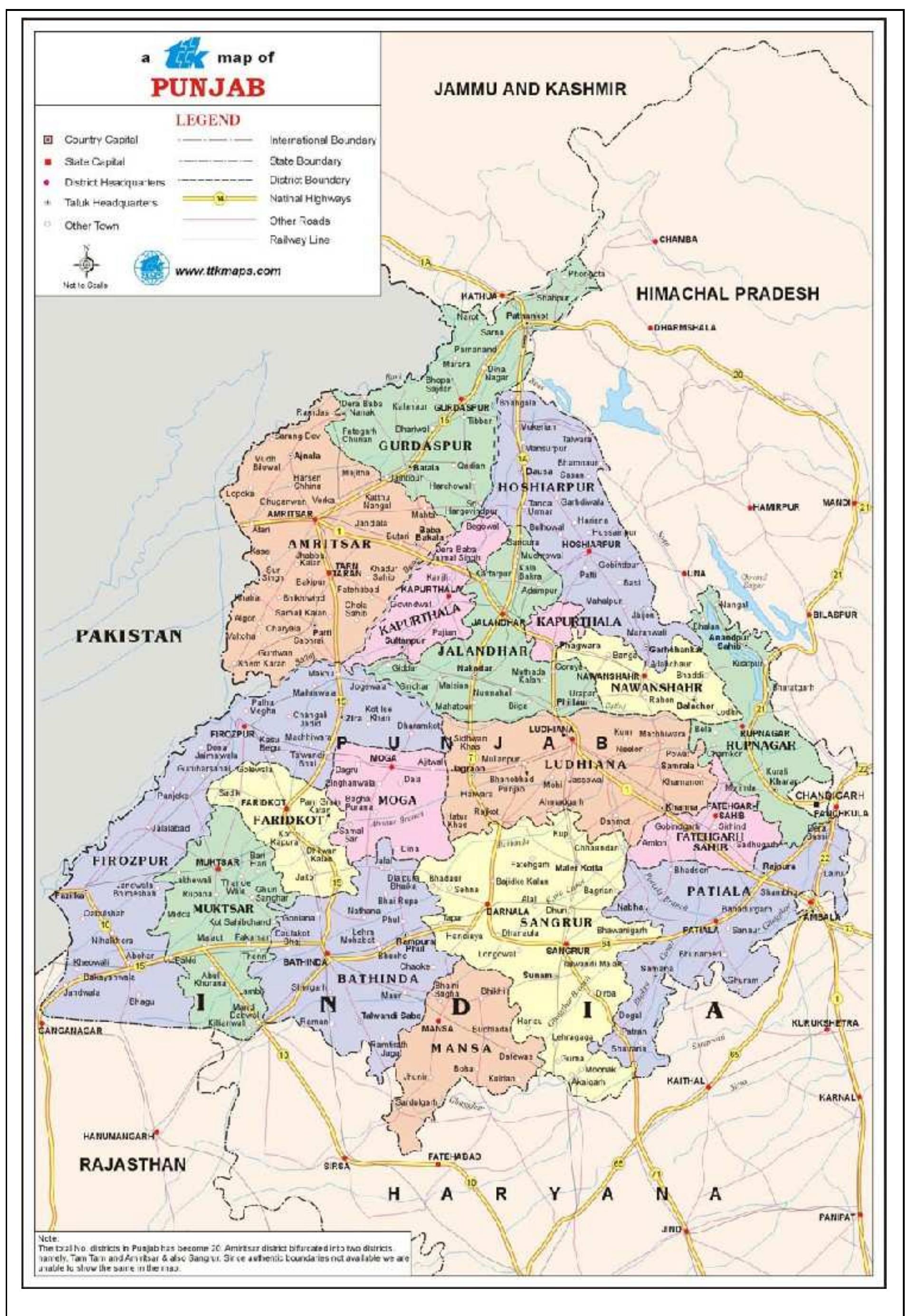

�Map of the Punjab

9

�Forces. When analyzing any insurgency, a simple comparison of forces and equipment gives

a distorted picture of reality. In the early phases of the insurgency the security forces are

greatly superior to the insurgents in most military metrics: firepower, mobility, numbers,

training, communications. But as historical examples and current experience have shown, this

does not mean at all, that the insurgents' position is hopeless. The imbalance in strength

slowly diminishes, until the insurgents achieve parity. Finally they become strong enough to

defeat the security forces in open battle and they can seize political power from the

constituted government.10

This model was partly applicable to the Khalistan insurgency, too. Although the security

forces were generally superior to the insurgents according to most military metrics, in the

early days of the insurgency they could not make good use of their superior strength, due to

inadequate information in the early stages of the insurgency. The insurgents managed to

create a viable clandestine armed force and challenge the government's power, and they came

close to success in 1984 and 1991 - even though this was due less to their own fighting

prowess than to mistaken decisions by the state and federal governments.

1981-84

1989

1990

1991

1994

60 000

70 000

security forces

local police

28 000

52 000

federal forces

70 000

25 000-40 000 ?

local militias

190 000 (?)

25 000

38 000

38 000

insurgents

(160 organizations)

4 000-5 000 ?

1 200

5 000

10 000

200-300 ?

forces to population

ratio

1/170

1/260

1/170

1/69

1/69

Table 1

Comparison of forces. (Source: Kang 2005, Gill 2001, Weiss 2002.)

But while the insurgents' recruiting base (Punjabi Sikhs) and external support (Pakistan and

the Sikh diaspora) were quite limited, the security forces could count on the resources of all

10

The above is a very short and inadequate sketch of Mao Zedong's model for revolution and guerrilla war.

10

�India, and could match and exceed the insurgents' growth of strength. When the federal

government decided to liquidate the insurgency without concessions or compromise (1992),

its forces managed to do just that within a few months.

The comparison of forces and equipment is only a part of the whole picture. Every insurgency

is a political struggle waged among the people, in order to obtain their support. This requires

constant presence among the people. Consequently, the necessary force levels are determined

not by the numbers or firepower of the insurgents, but by the population of the affected areas.

In peacetime the normal ratio of security forces to civilians is between 1:1,000 and 1:250.11 In

an emergency situation this ratio must be increased, and may reach 1:50.12 In the final stages

of the conflict the Indian security forces came close to this ratio in the state overall (see Table

1.), and since the insurgency did not affect all districts equally, they could achieve or exceed it

locally by temporary concentration of forces.

The Punjab state police (with a personnel strength that was 65 percent Sikh) played the most

fundamental role against the insurgents. In the course of the conflict the organization's

strength was increased nearly 300 percent, its vehicle park and communications equipment

was modernized. Over the opposition of many conservative officers police armament was

upgraded from bolt action Lee-Enfield rifles and Webley revolvers (mostly left over from the

period between the two world wars) to modern assault rifles and light machineguns.13 Locally

raised militias assisted the police in maintaining local security. Their numbers increased from

0 to nearly 40,000.

The central government - since it had doubts about the loyalty and reliability of the state

police - deployed internal security forces in the Punjab (e.g. Central Police Reserve Force

and Border Security Force) units. Their mission was partly to support, partly to keep an eye

on, the local police.

The mission of the military units deployed in the state was to deter or beat back a Pakistani

attack, but they often participated in counterinsurgency operations, too. Their physically fit,

11

In Hungary this ratio is 1:230, in Switzerland 1:390, in France 1:240, in Poland 1:380.

http://polis.osce.org/countries/

12

Quinlivan, James T.: "Force Requirements in Stability Operations," 1995. Parameters, Carlisle, PA, USA,

winter 1995, pp. 59-69, http://www.carlisle.army.mil/usawc/Parameters/1995/quinliv.htm

13

K.P.S. Gill: "Endgame in the Punjab"

11

�disciplined and seasoned manpower was particularly useful in establishing area dominance

and in cordon-and-search operations.

It is difficult to estimate the armed force of the insurgents - but this is true for every

insurgency; usually it is impossible to tell who is an active fighter, who is a less active

supporter, and who is a complete outsider that was forced to cooperate. Even at the height of

the insurgency the number of active fighters probably did not reach 10,000. A clandestine

network supported the fighters. The movement was fragmented: in 1990 the number of

insurgent groups was about 160, and occasionally the groups fought each other. This

fragmentation made coordination of the movement difficult, but it made the security forces'

intelligence and counterinsurgency operations even more difficult, because they had to divide

their forces (especially their intelligence resources). The insurgents used modern infantry

weapons (primarily AK47 rifles, RPG7 antitank rocket launchers) and standard military

explosives. Their primary source of supply was Pakistan.

The active fighters and supporting infrastructure was by several mass organizations (e.g. the

AISSF

All-India Sikh Student Federation, which had 300,000 members in 1981). The mass

mobilization activities of these organizations (strikes, demonstrations, street riots) supported

and supplemented the armed struggle.

Time. Experience has shown, that the modern state (especially the modern democratic state)

does not tolerate a protracted internal conflict, therefore its fundamental interest is to suppress

the insurgency as soon as possible. The insurgents, on the other hand - since they do not have

sufficient armed force to challenge the government forces openly - a protracted conflict seems

to offer the best chance of success.

The Khalistan insurgency, which started as the movement of a small and unpopular minority,

grew into a powerful movement and lasted 13 years primarily as the result of the uncertainty

and mistaken decisions of successive state and federal governments. First, they authorized the

use of indiscriminate force and mass arrests and drove many uncommitted Sikhs into the

ranks of the insurgents. Then they halted successful operations because they were seeking a

"political solution" - to which the insurgents' answer was further escalation of violence. When

determined governments were installed simultaneously at state and federal level, which could

12

�provide clear direction and political support to the security forces, the latter broke the back of

the insurgency, and suppressed it in hardly more than two years.

Intelligence. The goals of the Khalistan movement were well known, and its political leaders

were not difficult to identify. But the security forces needed a good deal more, and a good

deal more detailed information to suppress the movement: they had to know the leaders and

membership of the various armed groups, and the lines of communications between them; the

support networks, their procedures for population control and the names of people exercising

that control; the arms smuggling routes; the relationship and communications between the

clandestine armed groups and the legal political organizations, and a thousand other details.

In the early stages of the insurgency this information was not available, consequently the

security forces had to create a multisource local intelligence system with the participation of

the police, the paramilitary and military forces. The most important sources of intelligence

"raw material" were:

the periodic reports from the network of thanas (local police stations),

the detailed documentation of every terrorist incident,

the interrogation of captured insurgents and persons who operated the insurgency's

supporting infrastructure,14

technical means (voice intercept, remote observation),

double agents in the insurgent organization,

informants recruited among the population,

captured insurgents, who rallied to the government side.15

14

During the insurgency and subsequently the security forces have been often accused of using psychological

and physical coercion during interrogation. After fifteen years, and from a distance of several thousand

kilometers it is impossible to determine, who is telling the truth: the human rights organizations, the alleged

victims, or the policemen. However, this author's personal expereience as a HUMINT specialist suggests, that

some form of coercion is an essential element in every interrogation - there is absolutely no other way to

persuade an unwilling source to divulge information. Wether this coercion is subtle psychological pressure or

crude physical force depends on the skill and experience of the interrogator.

15

Using a combination of coercive and incentive measures (e.g. the promise of serious punishment for past

activities - or financial rewards and immunity) numerous insurgents were persuaded not only to furnish

information, but also to serve as active intelligence operatives and fight on the government's side. They were

called "Cats," based on the old English folk wisdom of "set a cat to catch a mouse." In the course of the

insurgency some Cats became regular policemen, and some have continued to serve in that capacity to this day.

Others were given new identities, and settled elsewhere in India or overseas. Mahadevan, Prem: "Counter

Terrorism in the Indian Punjab: Assessing the Cat System," Faultlines, Volume 18, January 2007.

http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/publication/faultlines/volume18/Article2.htm.

13

�Rapid analysis and dissemination of raw data meant actionable intelligence, and allowed

planning operations based on near real-time, and their execution with surgical precision.

Establishing area dominance and executing successful operations that did not affect the

civilians and caused no collateral damage started a self-sustaining process: the insurgents'

hold over the local population was broken; local security was established; more and more

civilians furnished up to date information to the security forces and cooperated in other ways

as well.

The insurgents' information posture was the opposite of the above scenario. In the early stages

of the insurgency they had near-perfect information on the activities, strength, movements,

command and intentions of the security forces. Their most important source of information

was a network of secret sympathizers serving in the ranks of the security forces (primarily in

the Punjab Police). The sympathizers gradually disappeared: there was no witch hunt, there

were no spectacular arrests or show trials (these would have created instant martyrs to the

cause and so would have been counterproductive). Those who came under suspicion were

discreetly (but very quickly) shifted to assignments where they had no access to operational

information.16 The insurgents' other main source of intelligence was the population - the

average citizen, who was compelled or enticed to cooperate. As the security forces established

territorial dominance, this source of information gradually dried up.

Information Operations

It may seem an anachronism to talk about "information operations" in the context of

Khalistan. At the time the insurgency was in progress the term existed only as a gleam in the

eyes of researchers at some American think-tank, but it did not yet exist as a military-political

doctrine that combines several disparate fields, with the intention of dominating the

information spectrum.17 But war (including counterinsurgency) is primarily a matter of

practice, with theory and doctrine generally following and codifying what has already been

tested in the field. So it was in the Punjab: neither the insurgents, nor the government had an

16

Mathur, Anant: "Secrets of Coin Success: Lessons from the Punjab Campaign," 2008, Air Command and Staff

College, Air University, Maxwell AFB, AL, USA, https://www.afresearch.org/skins/rims/q_mod_be0e99f3fc56-4ccb-8dfe-670c0822a153/q_act_downloadpaper/q_obj_871b3765-5017-40f6-a46618310df6496b/display.aspx?rs=enginespage

17

The earliest doctrinal publication the author was able to unearth with that title was FM 100-6 of the US Army.

14

�information operations manual or regulation - but both sides were well aware of the uses and

requirements of propaganda, and devoted considerable resources to it.

As in many insurgencies, the federal and state governments were at a disadvantage. The

Punjab was just one of many pressing issues on India's political agenda; the state government

also had many other concerns in addition to the wild-eyed adherents of Khalistan

an it was

not at all clear in the first place, whether the state's political elite really wanted to suppress the

insurgency, or wanted to harness it for its own purposes. For much of the period different

parties governed the state and the union

resulting in the usual differences and contradictions

one would expect. Therefore, the message of the governments was confused, confusing,

ambiguous, weak and often contradictory. In contrast, the insurgents had one single cause,

one single purpose, and one single message - Khalistani independence. The spirit of the age

was also on their side: revolutionaries, rebels, insurgents could do no wrong in the eyes of the

world's opinion-makers. They may commit unspeakable atrocities, mislead the press,

manipulate and strong-arm intermediaries, intimidate aid workers and "independent

observers" - they would still get the benefit of the doubt, explanations would be offered for

their questionable behavior, their callous disregard for some of the basic standards of

humanity would be excused.18 The government's version of events (especially when presented

by uniformed representatives of the security forces) would always be treated skeptically, even

when journalists are allowed free and unimpeded access.

Statewide censorship succeeded in muting the voice of Khalistan, but censorship is essentially

a negative tool, and it is no substitute for a positive message. In any case, it had to be lifted

or at least relaxed

during periods when the government was seeking a political solution and

reconciliation, and this offered opportunities for the insurgents to press home their message.

The two-year period of the V.P. Singh and Chandra Shekar governments (1989-91) is

particularly instructive: the Khalistani movement launched a masterful information operation

campaign, in tandem with escalating terrorism.19 The campaign's success, combined with the

18

The sitiation has changed very little in the beginning of the 2st centiury.

19

Most information in this section is based on Sahni, Ajai (2000): "Free Speech in an Age of Violence - The

Challenge of Non-governmental Suppression," in K.P.S. Gill and Ajay Sahni, editors: Terror and

Containment - Perspectives of India's Internal Security, Gyan Publishing House Ltd, New Delhi, India, 368 p.

SBN:81-212-0712-6, pp 161-182 and K.P.S. Gill: "Endgame in the Punjab"

15

�weakness and indecision of the state and federal governments brought the insurgents to the

brink of victory.

The insurgents issued a "Panthic Code of Conduct" for the media20 and demanded full

compliance from both official and private press, radio and TV outlets in the state. They

enforced the code through unbridled violence: editors, journalists, photographers, TV

announcers, even deliverymen and newspaper vendors were murdered, some with spectacular

brutality. Although the perpetrators were often arrested or killed in encounters with police, the

media (both the official, government outlets and the private ones) were thoroughly

intimidated: for a time every element of the Panthic Code of Conduct was unquestioningly

accepted by the official media, radio and television, as well as the national and regional

newspapers. To its credit, the government deployed significant resources (at times up to two

battalions of police) to support and protect the Hind Samachar Group, which was the sole

exception to the general media surrender.21

The insurgents' front organizations launched a campaign of civil disobedience and community

consciousness, backed by coercive mass mobilization. The gurudwaras in the villages could

not recover their status as safe-havens, but they served as outlets for the movement's

propaganda. Protest strikes became a daily occurrence and paralyzed life in urban areas.

Roads and railway tracks were blockaded. After every police action or arrest of an insurgent,

activists gheraoed22 police stations and senior police officials (and thereby provoked arrest).

Community consciousness was generated and strengthened by commemorative prayer

ceremonies for every insurgent killed by the police; by numberless anniversaries of "martyrs;"

by foundation-laying or inauguration of memorials in honor of felled extremists (memorials

that in the past had been erected only in honor of the greatest saints of Sikhism). These events

served as the building blocks in a mythology of sacrifice and martyrdom around the death of

20

"Panth" is the Sikh world community - a concept similar to the Muslims' umma. Some key features of the code

were: cetrain words and expressions (starting with atankvadi - the Punjabi word for terrorist) were banned;

broadcasts in languages other than Punjabi were prohibited; Khalistani press releases and propaganda material

had to be published or broadcast without amendment (or censorship, in the case of government media); a

number of changes in personnel and programming were required; women TV announcers were required to

cover their head when on the air.

21

The media group paid a heavy price for its principled stand: 62 of its associates (including the proprietor,

editors, journalists - but also street vendors) were killed during the insurgency.

22

Gherao is a Hindi word, meaning "encircle, surround." It is a common South Asian form of street politics and

protest. The target of the gherao (usually a public figure) is surrounded by a group of activists on the street.

They follow him and loudly demand his attention (actually rather the attention of the general public).

Obviously the task is much simpler, if the target is stationary like a police station.

16

�every fallen insurgent - even those who had been common criminals while alive. The crowds

that were necessary to add weight to these events were mobilized regardless of popular will:23

village councils were ordered to muster the requisite number of participants; trucks and other

vehicles were requisitioned to transport the people to the day's events; the public address

system of the village gurudwara made announcements at night, directing the villagers to

report at the appointed hour, with the unequivocal warning that disobedience would be met

with dire consequences - the message was clear, and compliance was total.

With the increasing intensity of the front organizations' activities, there was a progressive

blurring of lines between the legitimate and the illegitimate. Thumbing their noses at the

authorities, wanted insurgents openly attended the mass rallies, since the police could not

engage a handful of extremists within large gatherings of common citizens. If they did

intervene, loud protestations of "police harassment" were made at the highest levels.

The mass mobilization programs were supplemented up by an extensive and well coordinated

human rights campaign. Many of its activists were members of insurgent fronts, but many

others are best described by the Leninist label of "useful idiots," yet others as political

opportunists, trying to curry favor with the future winners. Fact finding committees consisting

of sympathizers and pro-militant politicians were set up after each police operation. At a time

when the insurgents were killing an average of over 200 people in a month, the human rights

activists questioned, discussed and investigated every police action, and declared most of

them excessive and unjustified. Every arrest victimized the innocent; every shootout but

especially those that ended in the death of an insurgent

was a "false encounter" and an

atrocity; "genuine encounters" did not exist. Soon the Punjab (and India, and the rest of the

world) was full of allegations of police atrocities; in every case, they were "known" to have

happened in "a village nearby" or some similar indeterminate location, and they were

invariably witnessed by a person other than the narrator.

The civil disobedience actions and mass rallies pinned down ever-increasing numbers of

security personnel and gradually reduced the force available for operational duties. The

effectiveness of those that remained was seriously reduced, because every action they took

23

This does not mean that popular support was totally absent. On the contrary, support grew continuously as the

mix of religion and politics, the rhetoric of the mass rallies touched a responsive chord among the rural

population.

17

�was under heavy (and malevolent) scrutiny, every mistake they made was assumed to be

intentional abuse of power. The reduction in the intensity of the security forces' operational

tempo offered new opportunities for violence, sabotage and disruption. Focused violence (that

by the end of 1988 had been confined to parts of three districts along the Pakistani border)

erupted again, and affected ever larger areas of the state. One of the most unsettling features

of the new campaign of violence was that it also targeted the families of the security forces.24

The insurgents' message was clear: there is no alternative to Khalistan; neither the

government, nor the security forces have the power to stop its creation; those who stand in the

way will be crushed. The combination of the information operation with focused violence

drove home the message far more effectively, than either component alone would have.

In many respects the protagonists were their own worst enemies in the area of information

operations: their actions, or the behavior of their adherents directly contradicted some or all of

the messages they were trying to project. The central government did not find the narrative to

counter the idea of Khalistani independence. Its dismissive attitude towards local Sikh

aspirations; heavy-handed military operations against brave, but poorly armed Sikh militants;

detention of Sikh leaders; martial law, emergency police powers, detention without trial;

terrorism courts with extraordinary rules of evidence; the suspension of some civil rights and

the institution of full press censorship

all these may have been essential for maintaining

control. But they were poorly communicated, and in the hands of skilled propagandists they

became further evidence of the central government s hostility to Sikhs, its shift from basic

democratic principles toward autocracy. They made the position of moderate Sikh politicians

untenable in the radicalized Sikh society.

But the Khalistan movement had its own share of failures in the information operations

domain, primarily due to its propensity for violence. The murder of Hindu passengers on

trains and buses, the assassination of political candidates, raping women in the villages that

gave them shelter, violent reprisal against all who would not toe the line the movement

24

Soldiers and policemen risk their lives but they do so knowing that their their parents, their wives, their

children are secure from violence, and that their own actions are in defence of the welfare of their families and

community. This is also the case in most counterinsurgencies, where sceurity forces are deployed from regions

outside the area of strife. In the Punjab, however, most security forces personnel were drawn from the state

many from the areas worst affected by the insurgency. Their participation in operations, the very act of

wearing a uniform, exposed their families to risk of retaliation, and subjected the men to mental stress that

fighting forces are ordinarily not required to confront.

18

�dictated, the very large number of Sikh victims of Khalistani violence were difficult to

reconcile with the movement's message that it was acting in the name of the Sikh religion and

on behalf of all Sikhs. The disparity between message and reality alienated much of the

movement's support by 1991-92.

Legal Framework

An insurgency is always an emergency situation - it cannot be resolved within the legal

framework of peacetime. The insurgents are well aware of the protection the law offers, and

they do everything in their power to exploit it. They can paralyze the justice system through

the intimidation of a few key individuals (judges, prosecutors, witnesses), and then continue

their activities with only a single risk factor: defeat in a shootout with the security forces. But

if their intelligence system is good, this risk can also be minimized. So, the security forces

need special powers appropriate to the situation. As a result of the many internal armed

conflicts in India, the creation and application of special legislation that fits the given situation

has become parliamentary routine. During the Khalistan insurgency six federal laws assisted

the security forces.

The National Security Act (1980) suspended some constitutional limitations on the

activities of the security forces and allowed the arrest and preventive detention for up to

two years of persons whose activities were harmful to India.

The Anti-Hijacking Act (1982) was a response to Sikh air-piracy. It mandated strict

punishment (up to life imprisonment) for hijacking. The law and the aviation security

measures instituted at the same time reduced Sikh air-piracy.

The Armed Forces (Punjab and Chandigarth) Special Powers Act, (1983) empowered

the officers and non-commissioned officers of the armed forces to employ deadly force in

the maintenance of public order, to arrest suspects, destroy the elements of the insurgents'

infrastructure and conduct searches without warrant.

The Punjab Disturbed Areas Act (1983) gave the same powers to the officers and noncommissioned officers of the police.

19

�A Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (1987) was the first Indian law

to treat terrorism as a separate issue (previous laws only expanded the powers of police

agencies). The law defined terrorism, created a new judiciary system to prosecute and

punish terrorism, prescribed new legal processes and gave new powers to the security

forces.25 The new procedures made the work of authorities easier: suspects could be kept in

custody longer; the identity of witnesses testifying "in camera" was not revealed; the rules

of evidence were also simplified - in effect, it was up to the accused to prove his

innocence. The punishments were also substantially increased (death penalty, life

imprisonment).

The Religious Institutions (Prevention of Misuse) Ordinance (1988). Temples, holy

places, places of worship and pilgrimage (of any religion) have a special status; they are

regarded with far greater respect, than in Europe or in the USA. The security forces very

seldom enter them in their official capacity. The Khalistani insurgents abused this respect

and used the gurudwaras as places of refuge, command centers, arms warehouses and

fortresses. The purpose of the ordinance was to prevent this practice.

One of the most important elements of the legal framework was that it gave legal immunity to

the security forces for the decisions they made and the actions they carried out under the

special legislation provisions. This contributed a great deal to the effectiveness of

counterinsurgency measures - but also contributed to the criticism directed towards the laws.

The combination of immunity and special powers gave wide scope to illegal behavior, which

could only be curbed by maintaining close command supervision and iron discipline among

the ranks - but supervision and discipline were not always perfect.

The Sequence of Events

1970's. With the separation of Haryana and Himachal Pradesh from the Punjab in 1966, the

long-desired Sikh-majority state was created. The Punjabi language and Sikh culture and

religion dominated, and alleviated the Sikhs' anxiety over assimilation by the majority

Hindu religion and culture. But the centralizing attempts of the federal government, the

25

Up to then terrorist were tried in the criminal justice system. This gave them significant constitutional

protections, allowed lenient sentences, and placed a major burden on the limited resources available for

investigation and evidence-gathering.

20

�opportunism of the Sikh political elite, the social and economic problems brought to the

surface by the "green revolution" served as fertile soil for the "back to the roots" agitators.

1980-83 Escalation. A radical preacher, Jarnail Singh Bhinrandwale stood at the center of

the movement for religious renewal.26 In his speeches on Hindu oppression, on the dark

machinations of the central government and the prime minister, on the bitter fate of the

Sikh nation, on the dangers of the modern world and assimilation, on the creation of the

independent Sikh state - unlike other radical Sikh religious leaders - he did not hesitate to

call for violence. His incitement found an echo in the imagination of many Sikhs - his

followers intimidated politicians and the average man of the street, and subverted the

justice system. The police - since it did not receive unambiguous guidance from the state's

political leadership - lost control of the situation,

and the radical movement slowly took over control

of the state. Bhindranwale established the center of

his terror campaign in the Harimandir Sahib of

Amritsar - the holiest of all Sikh temples. Many of

his decisions and actions contravened the

fundamental dogmas of the Sikh religion, but the

faithful tolerated even this from him. He stockpiled

arms and ammunition in the temple and from its

sanctuary openly defied the state and federal

governments. The police dared not enter the temple

complex, because it did not want to provoke the

Sikhs.27 Throughout the Punjab Bhindranwale's

followers did the same in all other gurudwaras.

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale

26

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale (1947-1984) toured the villages of the Punjab and urged his listeners to live

according to the traditions and moral code of the Sikh religion. His political ambitions (the establishment of a

sovereign Sikh theocratic state) put him on a collision course with the Sikh political elite. According to a

popular conspiracy theory, he was actually just a willing tool in the hands of the prime minister, Indira Gandhi:

Gandhi exploited the conflict between Bhindranwale and the Shiromani Akali Dal by supporting

Bhindranwale she expected to divide the Sikhs, and thus create an opportunity for her own Congress party to

gain control over the Punjab legislature.

27

India's security forces are anything but timid, but if they enter a temple in their official capacity rather than as

worshipers, if they want to enforce the law, rather than pray, they are easily accused of desecration of a holy

place, or inciting hatred and conflict between religious communities.

21

�1984. Operations Bluestar and Woodrose. By the

spring of 1984 the adherents of independent

Khalistan were murdering a dozen people a day in

the name of freedom; the new Khalistani currency

was being printed and distributed; Pakistan was

supporting the insurgents with money and arms. 28

A spontaneous exchange of population had also

started: Punjabi Hindus and other minorities were

moving to other states, while Sikhs from

neighboring states were moving to the Punjab in

increasing numbers. By May a declaration of

independence was expected any minute, and there

was a strong possibility that once independence

was declared, Pakistan would immediately

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi

(1917-1984)

recognize the new state, and send its forces across the border to guarantee its security.29

Finally Indira Gandhi ordered the armed forces to take back the Golden Temple and

suppress Bhindranwale's movement. The Army carried out the order: on June 5 1984 it

occupied the Golden Temple by force (Operation Bluestar). It was an inauspicious date for

the operation: it coincided with a Sikh religious holiday; thousands of pilgrims were in the

Golden Temple grounds when the assault begun, and the insurgents used many of them as

human shields. Bhindranwale and many of his associates were killed - but there were a

very large number of civilian casualties as well.30 Concurrently with Bluestar the security

28

Exactly as Indian forces did in 1971, when East Pakistan (today's Bangladesh) declared its independence.

Diwanji, Amberish K; Apar Singh Bajwa; Anil A. Athale: "Operation Bluestar, 20 Years on," Rediff, Mumbai,

India, 3 June 2004, http://www.rediff.com/news/2004/jun/03spec.htm.

29

Pakistan's support for the insurgents did not mean support for their goal of establishing a sovereign,

independent Khalistan. The Pakistani government regarded the Sikh insurgency as no more than a useful tool

for furthering its own goals in the region - especially in Jammu and Kashmir.

30

Diwanji et al. 2004. There was no way to execute the attack as an unexpected raid: there were 2-3,000 armed

insurgents in the Golden Temple, and the force necessary to defeat them could not be assembled by stealth.

Besieging and starving out the insurgents was not a realistic alternative: the Golden Temple is a huge complex

of buildings, with wells, and artificial lake, a food warehouse for feeding the pilgrims. Within the complex the

insurgents constructed reinforced firing positions. A disciplined garrison could have held out for months which would have been a certain failure for the security forces: the Sikhs are a warlike nation (the best,

bravest, most disciplined units of India's armed forces are the Sikh battalions) - within 48 hours thousands of

people, armed with rusty spear, swords and old rifles, would have converged on Amritsar to defend the holiest

shrine of their religion.

22

�Harmandir Sahib, the holiest temple of the Sikhs, in the center of a 150x150 m artificial

lake. NW of the temple is the Akhal Takht, seat of one of the fove temporal authorities of

the Sikh religion. The quadrangle sourrounding the lake and some of the outlying

buildings also belong to the temple. The attack was deliverd from three sides

simultaneously (white arrows), and culminated in taking the Akal Takht.

Source: www.google.com

forces begun to roll up the Khalistan movement's supporting infrastructure. In the course of

Operation Woodrose thousands of people were arrested. Since neither the police, nor the

federal intelligence services, nor the paramilitary and military units redeployed from other

states had much reliable information on the movement

many arrests were at random, or

based on the most tenous reasons (e.g. age).

Bluestar outraged the Sikhs all over India. Perhaps not many mourned Bhindranwale and

his followers, but most found it unacceptable that the armed forces desecrated the Golden

Temple. Sikh battalions mutinied, and many Sikh soldiers deserted; public figures returned

23

�their awards; civil servants in high positions resigned their posts; thousands of young men

crossed the border into Pakistan to join the Khalistani movement. Five months after the

operations two Sikh members of her security detail murdered Indira Gandhi. The murder

was oil on the fire: anti-Sikh riots broke out all over India and resulted in thousands of

victims. The riots were brought under control in a short time, but they further exacerbated

the polarization between Sikhs and Hindus, and motivated many more young men to join

the Khalistani movement.

1984-87. The Search for a Political Solution.

Rajiv Gandhi, the new prime minister (son of the

murdered Indira Gandhi) withdrew federal forces

from the Punjab and tried to make a deal with the

Sikh political elite. The deal was made (the

Rajiv-Longowal Accord of July 26 1985). Sikh

public opinion generally approved of the accord

and hoped that this was the end of the

insurgency. But the insurgents had other ideas,

and the Sikh political elite could not exercise any

influence over them. They responded to the

federal government's goodwill gestures (e.g.

release from detention of a large number of

insurgents) with a renewed wave of violence. A

Rajiv Gandhi (1944-1991)

few weeks after the accord was signed the politician who signed it, Harcharan Singh

Longowal was murdered, and terrorist attacks continued. The Punjab government was

unable to rein in the violence - the insurgents even managed to regain control of the

Golden Temple for a short time in 1986.

1987-89. Successful Counterinsurgency Operations. Gandhi had to acknowledge, that his

plans for a political deal failed, and he returned to a policy of force. The security forces

were successful. The insurgents were forced out of the Golden Temple again.31 As a result

of operations carried out under the command of Director General of Police Julio Ribeiro

31

Operation Black Thunder (April 1988) unlike Bluestar was carried out on the basis of sufficiently detailed

and accurate intelligence by the police and paramilitary forces. There were no casualties, and - perhaps even

more important - there was no damage to the Golden Temple.

24

�and Inspector General Kanwar Pal Singh Gill,32 the insurgency was confined to a steadily

decreasing area. By January 1989 only three districts along the Pakistani border (Amritsar,

Ferozepur, Gurdaspur) were affected. The insurgents were suffering heavy losses and they

had grave difficulties finding replacements. In spite of generous Pakistani assistance their

morale was shaken, and increasing numbers sought to make peace with the government but for political reasons Gandhi and the Congress Party missed the opportunity.

1989-91. Renewed Search for a Political Solution. The new prime minister, Visvanatah

Pratap Singh (himself a Sikh) returned to the search for a political solution. His gestures of

demonstrative respect for the Sikh religion, a slowdown in counterinsurgency operations

and offers of concessions only encouraged the insurgents. V.P. Singh's government soon

fell, but the next prime minister (Chandra Shekar) followed an even worse course of

action: he started direct negotiations with the insurgents and tried to achieve an agreement

from a position of weakness. This policy was worse than a failure - it brought the

insurgency onto the brink of success.

The insurgents exploited the security forces' reduced activity to reorganize their forces and

support networks, recruit new members and rearm. Additionally, their front organization

started a major information operation campaign using civil disobedience and mass

mobilization techniques to indoctrinate the ordinary Punjabis, while other organizations

mounted a successful media campaign to demonize the security forces. Violence also

begun to escalate again, and covered steadily increasing areas of the state. They also began

to target the families of security forces personnel. (See the section on Information

Operations, above).

The insurgents felt that they were on a winning streak, and would not negotiate on any

subject except the details of independence. They even managed to get rid of their most

effective opponent: K.P.S. Gill was transferred in December 1990.

1991-94. Determined Counterinsurgency. The Chandra Shekar government soon fell. The

new prime minister, Narashima Rao, considered resolution of the Punjab problem the most

32

A Director General of Police in the Indian Police Service is roughly equivalent to an army Lieutenant General,

and an Inspector General to a Brigadier General. In 1988. K. P. S. Gill was promoted and replaced Ribeiro as

the Punjab's senior policeman.

25

�important task of his government. He saw no chance for a political solution: there was no

political force in the Punjab that could fulfill any promise it may make. The Punjabi

political elite had no influence at all over the insurgents, and among the 160 or so

organizations of the fragmented insurgent movement there was not a single one that could

impose a solution on all. So Rao saw the use of force as the only possible solution.

Breaking with the habits of previous governments, he forbade all political interference in

counterinsurgency operations, sharply increased the federal forces deployed in the Punjab,

had K.P.S. Gill reassigned there as DGP in November 1991, and authorized the security

forces to use such force as they found necessary to suppress the insurgency As a result of

such firm and determined political support, in a few months of intensive operations the

security forces reestablished territorial dominance, regained control over the population

and seriously degraded the insurgents strength. Based on the successes of the security

forces, the government offered an amnesty in 1992, which about 10 percent of the

insurgents accepted. Leaders and ideologist of the movement found refuge in Pakistan. The

remaining hard core of insurgent forces was gradually destroyed in the course of the next

two years.

Insurgent Doctrine and Procedures

As all insurgencies, the Khalistan

movement also had two pillars:

violent action of the clandestine

armed groups was supplemented

and reinforced by the activities of

the more-or less legitimate mass

organizations.

The insurgents made their goal

crystal clear: to create an

independent, sovereign Khalistan,

Khalistani flag

where the Sikh religion informs

governance, Sikh culture dominates and Punjabi is spoken. They considered anarchy the best

way to achieve their goal: to cause the greatest possible chaos for the longest possible time

26

�through terrorist attacks, unbridled violence and mass mobilization actions, until Indian

society and government get tired of the fight and accept Khalistani independence - or until the

international community gets tired of the news of violence and atrocities coming out of the

Punjab and forces India to grant independence.

Armed groups carried out targeted assassinations. Sooner or later everyone considered

dangerous for the movement or an obstacle to Khalistani independence became a target.

Moderate Sikh leaders, Hindu politicians, editors and journalist who did not obey the

movement's demands were killed one after the other. The security forces and the village

militias, key personnel of the judiciary (judges, prosecutors) were permanent targets. As

happens in many insurgencies, the movement's violence often served individual interests.

Private scores were settled by denouncing private enemies as enemies of Khalistan; also,

Bhindranwale did not accept criticism

while he was alive, anyone who dared question his

behavior or views, who disagreed with his decisions immediately became a target. In the final

phases of the insurgency families of the security forces were also targeted.

Random surprise attacks served the purpose of mass intimidation and the expulsion of the

Hindus. Grenades were thrown into worshipping crowds during Hindu religious festivals;

motorcycle gunmen opened fire on market crowds; in industrial and business centers shooting

and bombing attacks were carried out against employees (primarily immigrants from other

states) and businessmen; Hindu passengers were killed on trains and long-distance buses.

Especially in the final phases of the insurgency, spectacular mass casualty attacks were

attempted.

Sabotage of the civilian infrastructure demonstrated the impotence of the government and

the security forces. Firebombs in railroad stations, bus terminals, post offices and other public

buildings degraded critical infrastructure and increased the general feeling of insecurity.

Criminal activities (bank raids, jewelery store robberies, extortion) served to finance the

movement, and also showed the citizen his vulnerability.

Legal front organizations, as mentioned above, mobilized the population through agitation

(and very often intimidation). They organized demonstrations and civil disobedience

campaigns, and organized the gheraos that are such a common feature of Indian street

politics. Their propaganda activities emphasized the dangers threatening Sikh religion and

27

�culture and lionized the movement's martyrs. Through manipulation of the press and the

human rights organizations they had considerable success in demonizing the security forces.

Security Forces Doctrine and Procedures

In the early stages of the insurgency the Punjab Police had no experience in handling an

insurgency. This deficiency could have been remedied relatively easily and quickly, but the

state's political and intellectual elites gave them no clear guidance. It was not clear at all,

whether either the state government or the opposition wants the insurgency suppressed, or

they want to exploit it for their own selfish political purposes. Some federal forces - especially

the paramilitary forces - had significant counterinsurgency experience, but were not familiar

with local conditions and had no information on the Khalistan movement. This institutional

ignorance led to the mistakes in Operations Bluestar and Woodrose.

When Kanwar Pal Singh Gill was assigned to the

Punjab as Inspection General (three months after

Bluestar and Woodrose), the situation changed

dramatically. Gill's selection was a stroke of genius the right man was assigned to the right place at the

necessary time. He was a fearless, strong and

charismatic leader and an experienced professional,

with many years of counterinsurgency experience.33

In addition to these personal qualification, he was a

deeply religious Jat Sikh.34 There was no way to

deceive him in matters of theology, because he was as

familiar with his religion's tenets as anyone. And he

could not be regarded as an outsider, either. Gill

DGP Kanwar Pal Singh Gill

accepted the basic principles of India's

counterinsurgency doctrine, but he had his own ideas about their application:

33

Kanwar Pal Singh Gill reported to the Police Academy in 1957. Following graduation he was assigned to

Assam, where he gained a lot of experience in fighting the local insurgency movement for 20 years. (Gill, 1987

és Mathur, 2008.)

34

Neither secular India, nor the Sikh religion recognizes the institution of caste - yet castes exist, and most

Indians pay close attention to them. Sikh society divides into about a dozen castes (plus a number of sub

castes). Jat is one of the higher castes.

28

�An insurgency must be resolved through political, economic, legal measures. But these

measures work only if they are applied in areas which are dominated and permanently

controlled by the security forces. Otherwise, they are worthless, because they do not

achieve their purpose, and their benefits are not enjoyed by their intended targets.

Therefore, security is the most important thing: peace and security must be established

and maintained for a long time (either by permanent presence of the security forces, or by

establishing local militias), and the people must be persuaded that peace and security will

be permanent. Non-military measures make sense only after these goals are achieved.

Genuine support for an insurgency is far less than what initial numbers and events suggest.

In reality, support is a community's survival response to the coercive measures deployed by

the insurgents - a sort of societal Stockholm syndrome. As the insurgents are neutralized,

as local security is established, as the population is isolated from the insurgents, so support

for the insurgency evaporates, support for the security forces and the government grows

and the flow of information increases dramatically.

Insurgency and terrorism are not law enforcement problems, but forms of warfare

therefore the insurgents cannot be defeated by the usual police measures. The traditional

police doctrine of "use minimal force, but only when all other means have already failed"

cannot be applied blindly. The very concept of "minimal force" must be reevaluated: force

must be proportional to the threat, and it must be applied when it has the best effect, not as

a last resort. At the same time, the "collateral damage" of civilian casualties must be

avoided - therefore the security forces must operate without heavy weapons - they cannot

use mortars, artillery or air strikes.

The weak point of every insurgency is the replacement of losses - if recruitment cannot

keep place with losses suffered in combat, the movement withers. Therefore the armed

force of the movement must be attrited at a rate that exceeds it regeneration capabilities - at

a rate that is intolerable for the insurgents, but politically sustainable for the government.

Today "politically sustainment" means that the security forces' operations should not

violate human rights or cause civilian casualties. These two requirements are best fulfilled

by adequate local intelligence and the security forces' disciplined behavior.

29

�Firm and determined support from the political elite is crucial for success. Accepting

"root causes" theories as justification and excuse for violent acts, seeking a "political

solution" at any cost, halting successful counterintelligence operations, making

concessions to the insurgents' demands, initiating negotiations from a position of weakness

- these are the signposts leading to massive failure.

Counterinsurgency has to be led from the front - senior officers do have to spend some

of their time in air-conditioned offices and manage their forces on paper. But they must

also get out in the field, inspect their forces, assess the situation on the ground, meet with

the people most affected by the insurgency: the civilians who find themselves between the

millstones of the insurgents and security forces. They must take the same risks as their

subordinates, who fight the insurgents every day.

In accordance with these principles, the security forces first created the multisource local

intelligence system already mentioned. Up-to-date intelligence allowed the security forces to

plan and execute their operations with surgical precision and avoid the "collateral damage" of

civilian casualties that is the bane of every counterinsurgency. Adequate intelligence

deprived the insurgents of their anonymity - which had been their best protection from

retaliation. Each major insurgent attack was followed up by a major counterinsurgency

operation: the responsible group was targeted not only in the Punjab, but all over India. The

detailed information available on the group's members, their possible contacts and safe

houses, extended families, friends and sympathizers allowed the security forces to mount

surveillance and pursuit operations that would either result in arrest of the perpetrators - or at

the very least seriously degrade the group's capacity to act.

Attrition of the insurgent forces was the goal of operations. Their primary targets were the

most active, most aggressive leaders of the insurgency: their arrest or death rapidly degraded

the efficiency of the armed groups, disrupted communications between groups and shook the

morale of the insurgents - especially those of other leaders that were still active, and still in

India. On the basis of intelligence known insurgents were categorized from "A" to "C." The

most determined, most dangerous insurgents were classified as "A," and were marked for

special attention. The security forces did not expend much effort to arrest them: their

"neutralization" usually meant death in a shootout or ambush. In contrast, they did try to arrest

30

�the less committed "B" and "C" categories, and once captured they tried to persuade them to

assist the security forces to neutralize their erstwhile comrades.

For attrition to work, a high

tempo of operations had to be

maintained. Patrols, temporary

mobile checkpoints and cordon

and search operations kept up

the pressure on the insurgents.

When there was no actionable

intelligence available, the

forces would often be used in

force demonstration operations.

"Focal point patrolling"

Night dominance operation

unexpectedly concentrated

significant forces and large numbers of vehicles in an area where insurgent activity had been

particularly brisk. The concentration of forces did not always serve any useful purpose - the

reason for their presence may be as banal as a leadership conference where all district

commanders had to be present. But tactical vehicles arriving from all conceivable directions,

the suddenly mushrooming checkpoints, the constant movement of patrols (especially at

night) created the impression of a much larger force than was actually the case. "Night

dominance" operations served a similar purpose: with constant night patrols, checks and

raids the security forces did not always achieve concrete results, but they managed to seize the

night - which traditionally belongs to the insurgents.

All this required manpower, which gradually became available as a result of several

concurrent measures: police tasks were rearranged,35 personnel strength was increased, local

militias were raised, and paramilitary and military forces were deployed. Cooperation

between police, paramilitary, military and militia forces exploited the advantages of each and

allowed an efficient allocation of resources. Gill's innovation, the principle of "cooperative

command" avoided the bane of all joint operations: the turf-wars and the problems of

35

Gill regarded static checkpoints a serious waste of manpower at best, and inviting targets for enterprising

terrorists at worst. Following Operation Black Thunder he gradually abolished them and assigned the

policemen to more active operational duties.

31

�seniority. Gill himself coordinated military and police activities with the commanders of the

three army corps deployed in the Punjab. Police Inspector Generals served as liaison officers

at each corps headquarters, and Superintendents of Police36 at each brigade. Army battalions